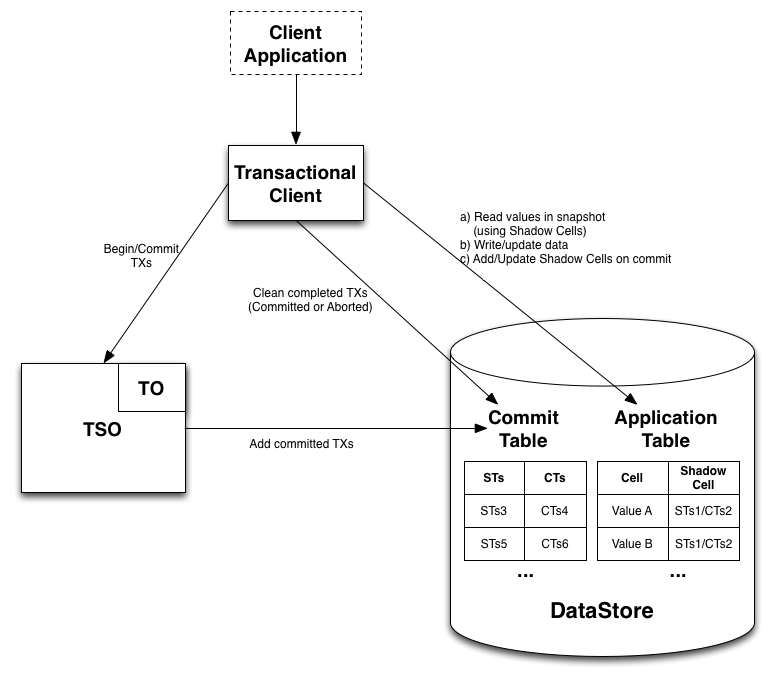

Omid Architecture and Component Description

The following figure depicts the current Omid architecture presented in the section presenting Omid:

The following sections describe more in deep the most important components and elements in the Omid architecture.

Transactional Clients (TCs)

Transactional Clients (TCs) are the entry point to user applications using transactions with Omid. They allow applications to demarcate transactional boundaries and read/write transactionally from/to the data source, HBase in this case.

There are two main interfaces/classes that compose the Transactional Client:

- The Transaction Manager interface (represented by the TransactionManager interface in the current implementation): Allows user applications to demarcate transactional contexts, providing methods to begin(), commit(), rollback() and markRollbackOnly() transactions.

- The Data Operation interface (represented by the TTable class in the HBase implementation): Allows user applications to trigger transactional operations to the datasource. For example in the HBase, put, get and scan operations.

Examples about how to add transactions using these interfaces are described in the Basic Examples section.

Timestamp Oracle (TO)

The single responsibility of the Timestamp Oracle is to manage transaction timestamps. Transaction timestamps serve as a logical clock and are used mainly to preserve the time-related guarantees required for Snapshot Isolation.

The TO allocates and delivers transaction timestamps when required by the TSO. To achieve this task, it maintains a monotonically increasing counter. Transaction timestamps are allocated when a transaction begins and right after a transaction willing to commit has passed the writeset validation. The start timestamp is also used as transaction identifier.

In order to guarantee that all timestamps are unique, the TO has to persist a value after every N timestamp allocations. This value will be used for recovering the TSO in case of crashes. The value persisted is the current timestamp value plus N, N being a congurable property. From that point on, the TO is then free to safely allocate timestamps up to that value.

In the current implementation, the maximum allocated timestamp value can be persisted/stored in:

- ZooKeeper

- In its own HBase table

The Server Oracle (TSO)

The TSO is the core component in Omid. There is a single instance of the TSO (Although a high availability protocol is currently a WIP). Its unique responsibility is to resolve conflicts between concurrent transactions. The TSO must maintain the last allocated timestamp, the so-called low watermark and a conflict map for detecting conflicts in the writesets of concurrent transactions. It also delegates the update and persistence of a list of committed transactions to the commit table component (see Figure). Aborted and uncommitted transactions are not tracked. Maintaining the TSO state to the minimum allows us to avoid contention in many cases and provides fast recovery upon crashes.

As mentioned before, conflict resolution for transactions is the primary function of the TSO. To achieve this task, it uses a large map structure of (cellId -> lastCommittedTransaction) pairs called the conflict map. When the client commits a transaction, it sends the cell ids of the cells being committed, i.e. its writeset, to the TSO, which checks possible conflicts when other transactions that were concurrent using the conflict map. If no conflicts are found, a commit timestamp is allocated and the lastCommittedTransaction for each cell id in the transaction is updated to this timestamp.

Confict detection is implemented by comparing the hash of the cell ids in the writeset, not the actual cell id value. As the conflict map does not have a one to one mapping with each cell in cell in the database, this means that there’s a possibility of false aborts in the system. The probability of false aborts is a variant of the birthday problem and basically translates into the fact that long-running transactions are more likely to have false aborts.

The low watermark is only updated when a value is replaced in the conflict map. The current implementation of the conflict map uses an open addressing type mechanism, using linear probing with a limit to the amount of probing. When a cell is checked it is hashed to a location in the map. If the location occupied, the location is checked and so on. If the cell finds an entry which matches its cell id, it replaces it. Otherwise, if the process gets to the end of the probe without finding an empty location, it replaces the cell with the oldest commit timestamp. The oldest commit timestamp then becomes the low watermark in the TSO. This must occur to ensure that conflicts are not missed, as it would be possible for a row to not find a potential conflict that had been overridden if the low watermark was not updated.

Processing Commit Requests

When processing the commit request for a transaction, the TSO first checks if the start timestamp is greater the low watermark and if so, if there was another concurrent transaction whose writeset overlapped and whose commit timestamp is greater the start timestamp of the requesting transaction. If no conflicts are found, a commit timestamp is generated for the request transaction which is added to the conflict map for the writeset, the commit is added to the commit table and finally the client is notified about the successful commit. Otherwise, the commit fails and the client is notied on the rollback of the transaction.

Commit Table (CT)

It contains a transient mapping from start timestamp to commit timestamp for recently committed transactions. The commit table is stored on a different set of nodes to the TSO. When a transaction is committed on the TSO it must be stored in the commit table before a response is sent to the client. As the key value mapping in the commit table are completely independent of each other, the table can be trivially scaled by sharding the values over multiple nodes.

The commit table provides two services to the Transactional Client. Firstly, it is used to check if a transaction has been committed or not. The client should not need to consult the commit table in the common case as the status of a read cell should be available from its shadow cell (see below).

The other service provided by the commit table is that transaction clients can delete commits from it. This only occurs once the writing client has updated shadow cells for each of the cells written in the transaction. We call this commit or transaction completion. It is possible that a client will crash between a transaction being committed and being completed. In this case, the transaction will stay in the commit table forever. However as the commit table is not stored in memory and the window of opportunity for such a crash is quite low, we don’t expect this to be a problem.

Shadow Cells (SCs)

Shadow cells contain a mapping from start timestamp to commit timestamp of the last committed transaction that modified the cell. Upon receiving a commit timestamp after a successful transaction commit, the Transactional Client adds/updates these special cells to each modified cell in the writeset of the committed transaction. The purpose of this, is that Transactional Clients can then query the corresponding shadow cell when they read each cell to check if the data they find in the cell has been committed or not and whether it is within the snapshot of the reading transaction.